- Home

- J. R. Jones

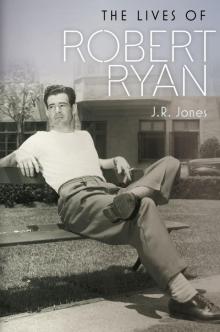

The Lives of Robert Ryan Page 12

The Lives of Robert Ryan Read online

Page 12

Enterprise approached RKO for a loan of Ryan and Barbara Bel Geddes, but Peter Rathvon, who had taken over as production chief temporarily, didn’t like the script and nixed the deal. Ryan must have been eager to make the picture; its producer, Wolfgang Reinhardt, was the son of his beloved acting teacher Max Reinhardt (who had died in 1943). After Einfeld invited Ryan over to the studio to discuss the situation, they placed a conference call to pitch the project to Hughes, who was notoriously hard to see in person. Hughes read the script and insisted that certain of his own idiosyncrasies (the sneakers, the rumpled clothing, the refusal to drink anything but milk) be deleted, but in the end he approved the loan. “Max could have Ryan and Bel Geddes,” Laurents recalled, “but the dailies had to be delivered to Mr. Hughes in person at his house at midnight by the editor.”14 When Rathvon learned that Hughes had overruled him, he resigned.15

By the time Ryan reported for work on July 30, Caught was already twelve days behind schedule; John Berry had taken over as director after Ophuls came down with shingles, but then Ophuls recovered, took over the picture again, and junked all of Berry’s footage. Enterprise was sliding toward bankruptcy after the recent flop of its Ingrid Bergman vehicle Arch of Triumph, and Ophuls was under serious pressure to get his picture back on track; the twelve days abandoned would have to be made up in four. Luckily for Ophuls, he had a trio of highly professional stars in Ryan, Bel Geddes, and James Mason, making his US screen debut as a compassionate ghetto doctor who completes the story’s love triangle. Mason was a superb actor, though according to Laurents he wore a false chest to make himself look more manly. Ryan, who had no need for a false chest, once confided to his friend Robert Wallsten that Bel Geddes came on to him before the shoot, explaining that she liked to sleep with her leading men. “I’m sorry to tell you,” Ryan replied, “but I have a wife and children.”16

Ophuls was himself a disciple of Max Reinhardt, and Ryan’s performance delighted him. “Max was very fond of Robert Ryan,” recalled assistant director Albert van Schmus. “He thought that he was a natural human being in front of the camera. And that’s what Max wanted, in that particular part at least.”17 Smith Ohlrig, the millionaire, was a complicated role; for the story to work, viewers would have to believe that Leonora had married him for love as well as money. When Leonora and Ohlrig first meet, he takes her on an aggressively fast midnight drive and interrogates her mercilessly, mocking her charm school training; Ryan captures the strange mix of charm, confidence, and vulnerability that made Hughes irresistible to so many women.

A later scene in a psychiatrist’s office tells a different story: Ohlrig is a serious head case, warped by his wealth and icy in his calculation of other people’s motives. He’s come to the shrink hoping to alleviate his recent heart trouble, and when the doctor suggests his attacks are an attention-getting device, Ohlrig leaps off the couch in a rage. “What are some of your other little gems?” he exclaims. “I must destroy everyone I can’t own? I’m afraid all anyone wants is my money? I’ll never marry because I’d only be married for my money?” To prove the doctor wrong, Ohlrig picks up the phone and directs an assistant to offer Leonora a wedding proposal.

Leonora soon finds herself confined to Ohlrig’s mansion on Long Island as he goes about his business and mercilessly antagonized when he deigns to come home — in one case, late at night, barking orders, with an entourage of business associates. His ensuing confrontation with Leonora plays out in the game room, where Ryan, in a wonderful bit of business, banks a billiard ball around the edges of a pool table as Ohlrig calculates Leonora’s motives for marrying him and her options for breaking free. “Every one of my corporations, every single one, has a different staff, a different lawyer, a different accountant,” he explains. “Not one of them knows anything about each other. I run it all. Each one has his place and he stays there…. And that’s what you’ve got to learn, Leonora. You’re better paid than any of them.”

BACK AT RKO, Ohlrig’s real-life counterpart was remaking the studio in his own image. Hughes had installed two of his men, C. J. Tevlin and Bicknell Lockhart, on an executive committee overseeing the studio, and through them he declared that the era of Dore Schary’s “message pictures” was over. Studio president Ned Depinet moved to New York to replace Peter Rathvon as corporate president, and longtime veteran Sid Rogell became head of production at RKO Radio Pictures. Yet the new owner’s management style caused no end of frustration. With his phobia of germs, Hughes kept counsel from his house or his office at the nearby Samuel Goldwyn Studio; RKO executives couldn’t reach him, which caused endless delays on critical decisions, but when he decided he was ready to talk, he would phone them at home in the middle of the night.

Cameras finally rolled again that fall as Hughes launched a slate of six modestly budgeted A pictures — the second of which, The Set-Up, began shooting in mid-October. Ryan had been coveting this assignment ever since he learned that RKO owned the rights to Joseph Moncure March’s pungent narrative poem. When it made the New York Times best-seller list in 1928, there hadn’t been an African-American heavyweight champion since Jack Johnson thirteen years earlier, and as March later observed, “The fight racket was still tainted by a strong residue of race prejudice.”18 Pansy Jones, the tragic hero of The Set-Up, is a black middleweight nearing the end of an undistinguished career,

A dark-skinned jinx

With eyes like a lynx,

A heart like a lion,

And a face like the Sphinx:

Battered, flat, massive:

Grim,

Always impassive.19

Pansy has lost so many fights lately that his manager doesn’t even bother to tell him when he cuts a deal with Tony Diamond, a local racketeer, for Pansy to throw his next bout. To everyone’s astonishment, however, Pansy comes on strong and knocks out his opponent. Walking home from the fight, Pansy is stalked by Diamond and one of his boys; they chase him down to the subway, where Pansy falls onto the tracks and dies under the wheels of a train.

Soon after publishing The Set-Up, March had come to Hollywood as a screenwriter and contributed story and dialogue to Hughes’s early triumph Hell’s Angels; since then, however, he had fallen into an unbroken run of forgettable pictures. When he heard that The Set-Up was being produced, he offered his services to RKO, but instead the job went to first-timer Art Cohn, a former sportswriter, and Pansy Jones became Bill “Stoker” Thompson, a two-bit fighter who has spent twenty years getting pummeled in bottom-of-the-card bouts. Julie, his disillusioned wife, begs him to retire before he gets killed, but Stoker still dreams of getting a title shot and thinks he can beat Tiger Nelson, the young up-and-comer he faces that night in the heartless tank town of Paradise City. “I thought the story was wonderful,” Ryan later told an interviewer, “because it had none of the usual mawkish glamour that is falsely attached to prize fight stories. It’s not a glamorous business.”20

RKO offered the script to Fred Zinnemann, but after Act of Violence the director was tired of brutality. Instead the job went to Robert Wise, an RKO contract director who had gotten his start as an editor (The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons). In keeping with the poem, Wise wanted the hero to be a black man, and he had his eye on Canada Lee, a former boxer who had played John Garfield’s sparring partner in Body and Soul. But at that point no black actor had ever starred in a big studio release, and as Wise recalled, Ryan was “dying to do it.”21 Even without the racial element, The Set-Up could be a relevant picture, exposing the seedy world of small-time boxing: the corruption, the bloodthirsty crowds, the athletes chewed up and spit out.

Wise and Cohn had plenty of time to research the picture while RKO was shut down. They saw fights at Hollywood Legion Stadium, and Wise toured the small arenas in Long Beach, observing the crowds and hanging out in the dressing rooms with the fighters.22 The Set-Up would be heavily populated with vivid minor characters: Shanley (Darryl Hickman), a nervous teenager facing his first prof

essional bout; Luther Hawkins (James Edwards), a black boxer in his prime, his route to the top all mapped out; “Gunboat” Johnson (David Clarke), an old-timer with a face full of scar tissue who leaves for the ring promising he will be champ someday and returns on a stretcher, unable to remember his name.

At the center of this ensemble, however, was Stoker Thompson, a dull-witted, good-hearted man and the most sympathetic figure Ryan had ever played onscreen. “I liked the character of Stoker,” he later wrote. “I liked his decency in a pretty grim business.”23 Ryan’s moving performance was even more impressive coming on the heels of Caught: Smith Ohlrig is rich, ruthless, and articulate, whereas Stoker is poor, empathetic, and plainspoken. Except for his opening argument with Julie (Audrey Totter) in their cheap room at the Hotel Cozy, his dialogue is sparse and mostly functional, which forces Ryan to communicate almost everything about the character physically. In the lengthy dressing room sequence he hugs the periphery, watching the other fighters and silently weighing the price he’s paid for a life in the ring.

After the fashion of Alfred Hitchcock’s recent mystery Rope, The Set-Up would transpire in real time, from 9:05 to 10:16 PM, with the four-round bout between Stoker and Tiger Nelson commencing at the midpoint of the picture. Ryan had boxed on-screen already in Golden Gloves and Behind the Rising Sun, but this would be his most demanding match. “I had to learn to fight like a professional instead of an amateur, and that took months of training,” he wrote.24 He and Hal Baylor, playing Nelson, rehearsed carefully with fight choreographer Johnny Indrisano, a former welterweight boxer who had found a second career in Hollywood. Wise spent about a week on the scene, using three cameras — one for a long shot, another for a two-shot, and a handheld camera to crowd the fighters — and edited the sequence himself. The result was thrilling, more intense and chaotic than any boxing match ever filmed. One former prizefighter on the set told Ryan, “This is so true it makes me sick.”25

The photojournalist Weegee (aka Arthur Fellig) was cast in a nonspeaking role as the timekeeper, and in a story for the Los Angeles Mirror he described the shoot as “a social register of the fighting racket,” observed by no less than eight former professionals. “HOW THAT GUY CAN FIGHT,” Weejee said of Ryan. “Usually on a fight story the make-up men (they prefer to be called ARTISTS) are busy painting on BLACK EYES … but here it was different … they were busy painting OUT real black eyes, as the fighters forgot about the camera and were really slugging it out.”26 Stoker is supposed to go down in the third round, but he hasn’t gotten the message and gives Nelson a run for his money. Back in Stoker’s corner, his manager (George Tobias) and corner man (Percy Shelton) spill the beans about the fix and beg him to lie down, but by now the struggle has taken on a life of its own.

Stoker wins by a knockout in the fourth, cheating the stony-faced racketeer Little Boy (Alan Baxter) out of the dive he was promised. As soon as the fight is over and the arena empties out, the power dynamic is suddenly reversed; when Stoker learns that his manager and corner man have vanished, the victory drains from his face, leaving only fear. Little Boy and his goons pay Stoker a visit in the dressing room, now silent and nearly deserted, and the racketeer promises they will be waiting for him outside. Once they’re gone, Stoker races through the arena in a panic* and tries to escape into the alley, but they’re waiting for him, along with Tiger Nelson. They close in, backing Stoker up against the corrugated metal shutter of a loading dock, his face slack with terror. For an actor such as Ryan, whose strength was key to his screen persona, it was a shockingly vulnerable moment. He would never have another quite like it.

“He takes more pride in that movie than any other he ever made,” Jessica Ryan wrote. “It was an original.”27 Howard Hughes certainly thought so: the following March, as RKO was readying the picture for release, he sued United Artists for copyright infringement, arguing that its forthcoming drama Champion (directed by Wise’s friend Mark Robson) duplicated key scenes from The Set-Up. A federal judge ruled for Hughes, ordering UA to delete from Champion a sequence in which the hero (Kirk Douglas), who has refused to throw a fight, is stalked and beaten by hoods. The Set-Up opened to glowing reviews, and that fall it won Wise the FIPRESCI critics’ prize at the Cannes Film Festival. But it would be snubbed at Oscar time, possibly because Hughes had rankled so many industry people by going after UA. Champion, however, was nominated for five Oscars, including Douglas as best actor.

“This is so true it makes me sick,” one former prizefighter told Ryan during production of The Set-Up (1949). The boxing classic would become a primary inspiration for Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980). Franklin Jarlett Collection

Stoker Thompson, cornered by Little Boy and his thugs, at the climax of The Set-Up (1949). “It had none of the usual mawkish glamour that is falsely attached to prizefight stories,” Ryan observed. “It’s not a glamorous business.” Film Noir Foundation

There were compensations. One night, after a preview screening at the studio, Ryan was approached on the street by Cary Grant. “You’re Robert Ryan,” Grant said, offering his hand. “My name’s Cary Grant.” The self-introduction was almost comical: Grant was one of the most famous movie stars in the world, and Ryan had admired him for years. “I want you to know that I just saw The Set-Up,” Grant went on, “and I thought your performance was one of the best I’ve ever seen.”28 Ryan never forgot the experience.

WHAT SPARE TIME RYAN HAD during The Set-Up went into the 1948 presidential campaign. President Truman was running against Thomas Dewey, the Republican governor of New York, but also was being challenged on the right by Strom Thurmond, who had led a walkout of Southern Democrats from the convention over the party’s new civil rights plank, and on the left by Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace, whom Truman had fired from his cabinet two years earlier. Wallace wanted to give equal rights to women and racial minorities, abolish the Un-American Activities Committee, and dismantle America’s nuclear arsenal, all attractive positions to Ryan. Yet he was going with Truman. Years later, in notes for a magazine article, Jessica Ryan would remember her husband’s insistence that votes for Wallace would only throw the presidency to the Republicans. “Through those years, he repeated again and again the dogma he had been raised on, Vote the Party, not the Man.”29

Wallace’s man in Hollywood was John Huston, director of The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, and Key Largo. Philip Dunne, who had formed the Committee for the First Amendment with Huston, recalled that “when John took on the job, the only people who were really supporting Wallace out here were the Hollywood Ten. They were all going around with big ‘Wallace in ’48’ buttons on. But nobody was supporting Truman very much, either. Bob Ryan and Dore Schary and [screenwriters] Lenny Spiegelgass, Allen Rivkin, and I were about the only liberals who were doing anything for Truman.”30 Ultimately, Wallace’s candidacy generated more excitement in Hollywood; Jessica would remember a banquet for Truman that failed to attract any more star power than her husband and Alan Ladd, “while Henry Wallace was wreathed in beauty glamor and fame.”31 But in the end Truman won, carrying Los Angeles and the State of California and dominating the electoral map against Dewey in a stunning upset.

The campaign impressed upon Jessica how hardheaded her husband’s politics were. When she had met him in the late ’30s, he had been full of colorful stories about Chicago ward heelers, though at that point he seemed disengaged from it all, more focused on acting and the theater. “But when he came to a broader political consciousness during the war and afterward, he came to it with an infinitely greater sophistication and sense of reality than the intellectual and artistic liberals we met in Hollywood had…. He approached the issues, always, with an insistence on what was possible, what would work … with a degree of frustration and often contempt for the vagaries of the liberals who spent immense amounts of energy talking endlessly about things that ought to be done, but obviously could not be done in the framework of how things got done. I think that n

either one of us were ever liberals in that sense of the word.”32

After The Set-Up wrapped in mid-November, Ryan found himself without a pending assignment for the first time in nearly two years. Production at RKO was proceeding at a snail’s pace under Hughes, who managed to appease the studio’s distributors by doling out the fifteen completed pictures Schary had left behind. One of these was The Boy with Green Hair, which had finished shooting eight months earlier but sat in limbo as Hughes tried to turn its pacifist philosophy inside out. Director Joseph Losey remembered an endless succession of notes from Hughes, written in pencil on yellow scrap paper, with orders for recutting the picture, but Losey had shot so little excess footage that not much could be done without reshoots.33 When the strange boy in the forest admonishes Dean Stockwell that war is harmful to children, Hughes wanted Stockwell to reply, “And that’s why we must have the greatest army, the greatest navy and the greatest air force in the world.”34 The twelve-year-old actor refused.

Three months and $150,000 later, RKO executives and board members screened the new version, which was so bad they persuaded Hughes to bite the bullet and release The Boy with Green Hair in something close to its original form.35 Losey stated later that only a few lines of offscreen dialogue were struck, though as he recalled, all the publicity “sort of militated against it because it made it appear to be a more important film than it was.”36 Reviewing the picture in the New York Times, Bosley Crowther called it “a novel and noble endeavor” but also “banal” and “weakly motivated.”37 Still, it was warmly received in liberal quarters, not least the Ryans’ dinner table. “For some reason The Boy with Green Hair was a movie that had a big presence when I was a kid,” Cheyney Ryan remembers.38

The Lives of Robert Ryan

The Lives of Robert Ryan