- Home

- J. R. Jones

The Lives of Robert Ryan Page 14

The Lives of Robert Ryan Read online

Page 14

Ray wanted to relocate the story to the United States and envisioned a prefatory sequence showing Wilson as a cop driven to savagery by the ugliness and venality all around him. To adapt Mad with Much Heart he recruited screenwriter A. I. Bezzerides — “Buzz” to his friends — a Greek-Armenian immigrant who had grown up in Fresno, California, and published a hard-boiled novel about truckers, They Drive by Night,* that was adapted to the screen for George Raft and Humphrey Bogart. Since then Buzz had become a screenwriter himself and adapted his novel Thieves’ Highway for director Jules Dassin. Ray sold him on the idea of riding with big-city cops to learn what their daily lives were like; Bezzerides spent a few nights with the LAPD, and Ray, visiting the East Coast, rode with Irish cops in Boston. In New York, Ray saw Sidney Kingsley’s new play Detective Story, which also dealt with a brutal cop in a big-city precinct.

“We start with the cop in the city being called up for his violence,” Bezzerides remembered. “He’s a vicious cop, vicious to criminals because he can rationalize it. Criminals are criminals to him, they’re not people. So he’s sent out of the city for his behavior, into the mountains.”20 The urban section, shot in Los Angeles, would take up the first half hour of an eighty-minute picture, and its tone was uniformly harsh, its city a nocturnal cesspool of drunks, hookers, and hustlers. The ostensible story line, a police procedural in which Jim Wilson and his two partners search for a cop killer, was simply dropped when the action moved out to the country; the real narrative was psychological, a series of encounters with urban lowlifes that exposed Wilson’s disgust with humanity.

The bifurcated story made Houseman uneasy, but for Ray it was the key to the picture: he even wanted to heighten the contrast by shooting the city scenes in black and white and the natural scenes in color (an idea the studio quickly nixed). Ryan signed off on the script, and on Monday, March 27, he set off from Union Station in Los Angeles to Denver, Colorado, and from there to Granby, Colorado, in the Rocky Mountains. According to Ray biographer Bernard Eisenschitz, “Ryan was in a scene as soon as he arrived, at 4:30 in the afternoon.”21 Ida Lupino, a luminous actress (High Sierra) who had become one of the few women directors in Hollywood, was cast as Mary, and Ward Bond, a hard-line anticommunist active in the right-wing Motion Picture Alliance, would play Bond, renamed Walter Brent. For Danny, the frightened man-child on the run, Ray managed to sneak in his nephew, Sumner Williams (whose anguished, inarticulate performance hinted at the work Ray would coax from James Dean in Rebel without a Cause).

Staying at the El Monte Inn, the cast and crew got a warm reception from the townspeople of Granby and nearby Tabernash, some of whom appeared in the film. Ray would remember the Granby shoot as a wonderful experience, and Ryan was sufficiently at ease there to show up at the local high school, speak to the boxing club, and sign autographs. Heavy snowfall impeded the two-week shoot, and at one point the generators broke down and the camera tripods began to freeze up. But the fresh snows created a blinding whiteness for the chase scenes, and the mountain terrain was stirring, a stark backdrop for the contest between Wilson and Brent over whether Danny will be apprehended or executed.

Back in Los Angeles, the focus shifted to the interiors and later the city locations, where Ray and Ryan really began digging into their embittered hero. The picture was ahead of its time in noting how cops are isolated and worn down not only by the repellent characters they deal with every day, but also by the fear and contempt of law-abiding citizens. Prowling the streets, Wilson and his two partners think they’ve spotted their man, and Wilson runs him down; a crowd gathers, but the guy is clean. “Dumb cops!” he blurts out angrily. “I was only running.” Wilson has to be held back from clocking the guy, and the policemen retreat to more snide comments from the crowd. Shortly after this altercation the trio stop at a drugstore, where Wilson sits at the soda fountain and flirts with the counter girl. When someone teases her about her boyfriend, she replies, “That’s all he’d need to know — me going out with a cop.” Wounded, Wilson spins around on his stool to hide his face, and his mouth tightens in resignation.

The night is full of users. At a dive bar Wilson is trailed by Lucky (Gus Schilling), an alcoholic trembling for his next drink, and gets hit on by an underage B-girl (Nita Talbot). At a side table a balding, bespectacled, obscenely grinning man (played by Bezzerides) tries to force some money on Wilson. Searching for a suspect named Bernie Tucker, Wilson pays a visit to Myrna (Cleo Moore), a slatternly platinum blond who shows him the bruises Tucker left on her and insinuates that he can leave a couple of his own if he likes. “The dissolve at the end of [the scene] will be played in such a way as to avoid the direct impression that Jim is about to indulge in a sex affair with Myrna,” Joseph Breen, head of the Production Code Administration, had instructed Harold Melniker of RKO.22 Ray cross-fades to a shot of Wilson coming down the stairs of the apartment building alone, but the sexual implication hangs in the air.

Breen was even more concerned about the graphic scene in Bernie Tucker’s apartment, where Wilson corners the suspect. Bernie, a grinning slimeball, dares Wilson to hit him, but his smile fades when he realizes he’s taunted the wrong man. “Why do you make me do it?” Wilson sputters, his voice rising in desperation. “Why do you make me do it? You know you’re gonna talk. I’m gonna make you talk! I always make you punks talk! Why do you do it? Why? Why?” In an era when studio releases were subjected to additional censorship from local boards, Breen pointed out that the ensuing beat-down “would unquestionably subject the picture to extensive cutting and possibly even rejection, especially in the many municipalities where censor control is exercised by the police department.”23 In the release version Ray fades out as Wilson comes down on Bernie, but no on-screen punch could be as unnerving as his twisted reasoning: Why do you make me do it?

The picture supplied Ryan with not only his most demented on-screen moment but also, ironically, the most moving love scenes he had ever shot. Ryan liked Lupino; as the blind Mary, she invested what might have been a mawkish character with an arresting combination of strength and empathy. When Mary asks Wilson what it’s like being a cop, he confesses, “You get so you don’t trust anybody.” Mary replies, “You’re lucky. You don’t have to trust anyone. I do. I have to trust everybody.” Lupino disliked the downbeat ending, which showed Mary alone and weeping after Wilson returns to the city, and Ray was sufficiently swayed to let her and Ryan improvise a new one in which Wilson turns around and comes back, and the characters are reunited.

Ray had elicited mesmerizing performances from both his leads. To hear Ryan tell it, Ray never gave him explicit instructions, which was fine with him. “I hate film-makers who want long discussions with actors over a scene,” he explained. “An actor who doesn’t know what a scene he’s going to play is all about is in the wrong profession. Nick had, I think, great respect for me. Right from the start of our collaboration, he only offered me a few suggestions.”24 Mostly Ray would tell Ryan about the Irish Catholic cops he had ridden with in Boston and how they had behaved in certain situations, and then let him take it from there.

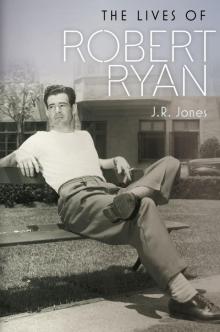

Ida Lupino and Ryan in On Dangerous Ground (1952). His role as an angry, despairing cop supplied him with not only his most demented screen moment but also the most moving love scenes he had ever shot. Film Noir Foundation

In Wilson’s apartment, the dresser is decorated with high school athletic trophies and a crucifix, evidence of the personal route Ryan was taking into his damned character. He had long since left the church, but the church had never left him; raised by Jesuits, he had come to manhood believing in the horrible stain of original sin, the sin of Adam, which had corrupted mankind forever. Lamont Johnson would remember commiserating with Ryan over “the hangovers that we both shared as ex-Catholics.” These involved “a hell of a lot of residual anger that I have, and I could sense that that was part of what there was with Bob…. I mean, we all had other things too, you can’t blame it all on the Catholic Church, but it was certainly a c

onsiderable portion of it, and you would see Bob just retreating into a cynical, cold, and conceivably dangerous guy in some moods. [He] was by no means the great, good-hearted Herbert that a lot of people think.”25 Whatever repressed rage Ryan may have been carrying around came bursting out in Mad with Much Heart. Then, like any other job, it was over, and he went home to his wife and kids.

FOUNDED IN 1947 on the University of California campus in San Diego, the La Jolla Playhouse had become a magnet for movie actors looking to get back onstage. Ryan had appeared there in the romantic farce Petticoat Fever in summer 1949, and on July 4, 1950, he returned to play the low-rent tycoon Harry Brock in a six-day run of Garson Kanin’s comedy Born Yesterday.

At one performance Jessica met Irene Selznick, the wife of producer David O. Selznick and daughter of MGM lion Louis B. Mayer, and over a drink in the Valencia Hotel, the two women started talking about their children and the chronic school overcrowding in California. Since the war began, the state population had swelled by 3.5 million, and there was an ongoing shortage of teachers and classrooms. Schools in Los Angeles County were operating on double shifts, with students receiving only a half day of instruction; one school had four kindergarten sessions stacked up from morning to late afternoon.26 The US birth rate had spiked in 1946, increasing nearly 6 percent, and a year from now those children — including Tim Ryan — would all be old enough for kindergarten.

Jessica mentioned that her pediatrician, Siegfried Knauer, had suggested she start her own school, and to her surprise, Selznick explained that during the war she had done just that: “You get together some children and find a place. Then you get a teacher to run it.”27

Years later, in a memoir about the founding of the Oakwood School, Jessica would trace her interest in starting a school to her own insecurity. “My hang-up was a simple one: I felt I had not had enough education. Meaning college. With the passing of time this want had become, family and friends tell me, something of an obsession.”28 Robert had to drive out to Kenab, Utah, in August to shoot locations for an RKO western called Best of the Badmen, but not long after his return, Jessica talked him into meeting with Tim’s nursery school teacher to discuss the idea. The teacher referred them to Sidney and Elizabeth Harmon, similar-minded parents who lived in nearby Studio City and had four children, and the two couples got together for cocktails.

Cheyney, Jessica, and Timothy Ryan (circa 1951). Robert Ryan Family

“Lizzie was a small, pretty woman with a breathless manner and childlike eyes that gazed with some bewilderment on the world,” wrote Jessica. Sid Harmon “wore horn-rimmed glasses on myopic brown eyes that looked warmly upon all the people he liked which, together with a fondness for talking, often made him resemble a benign rabbi.” In fact, Harmon was a producer — in the early ’30s, he had mounted a Pulitzer Prize-winning production of Sidney Kingsley’s Men in White with the Group Theatre, and a few years later he had come out to California to break into the picture business.* Lizzie had attended the private Ethical Culture Fieldston School in New York City, whereas Sid, like the Ryans, had gotten his primary education at public schools. The two couples agreed to host an open meeting for interested parents at the nursery school where Tim was enrolled with Andy Harmon.

Through director Joe Losey, the Ryans met producer Frank Taylor and his wife, who had started the Westland School near Beverly Hills; they sent the Ryans to meet its director, Lori Titelman. “Her advice was refreshingly uncluttered and to the point,” wrote Jessica. “In starting a school we must make up our minds to call a spade a spade — meaning, calling progressive progressive, even though the word had lately become suspect in both its educational and political context.”29

Progressive was a code word for communist, yet progressive education was actually rooted in the philosophy of John Dewey, embracing the notion that children learn better when engaged with the world around them. When the parents’ meeting at the nursery school took place, drawing in about fifty people,30 someone asked Ryan if he was proposing a progressive school. Winging it, he replied, “Modified progressive.” Harmon expressed the idea that the school would be open to all races and religions, to which someone commented, “Sounds pinko to me.”31 That first meeting did flush out one more interested couple: Ross Cabeen, a ruddy-faced petroleum engineer and rock-ribbed Republican, and his wife, Wendy. Cabeen “was out to make a great deal of money,” Jessica recalled. “But he was bugged by a conscience (partly his wife) telling him that he should do more.”32

A second parents’ meeting was called, with Lori Titelman as guest speaker, but her left-leaning philosophy and the idea of opening a racially integrated school seemed to scare off many of those attending. By this time loyalty oaths had become part of civic life in California, required of municipal and county employees as well as faculty and staff at state universities; that fall the Regents of the University of California had fired twenty-six tenured professors who refused to sign. The Levering Act, which passed the California legislature weeks later, barred state employees from collecting their checks unless they signed a statement denying membership in any organization deemed subversive by the US attorney general.33

Communism had become a hot issue in the 1950 midterm elections, especially after North Korean forces crossed the thirty-eighth parallel into South Korea in late June. In California, Democratic Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas — a former actress married to movie star Melvyn Douglas — was running for an open Senate seat against Republican Congressman Richard M. Nixon. As a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee, Nixon had come to prominence investigating whether former US State Department official Alger Hiss had passed secrets to the Soviet Union, and his work had led to Hiss being convicted of perjury. Nixon decided to make his anticommunist credentials central to his campaign, one so cunning in its attempts to smear Douglas that it would forever saddle him with the nickname Tricky Dick. The masterstroke was a flyer, printed on pink paper, that compared her voting record with that of New York Congressman Vito Marcantonio, widely thought to be a communist. A half million copies of this “Pink Sheet” were distributed across Southern California.

Ryan stumped for Douglas and contributed two hundred dollars to her campaign,34 but for the most part the Hollywood community shied away from her. Nixon, grasping the power of television, finished out the election cycle with a flood of commercials in which he accused Douglas of being soft on communism. A whispering campaign against her husband insinuated that he had changed his name from Melvyn Hesselberg to conceal his father’s Jewish roots in Russia. In the end Nixon clobbered Douglas, winning 59 percent of the popular vote. “There, in that murderous character assassination campaign,” wrote Jessica, “we saw that the horror of what had been going on in Hollywood with the rise of the blacklist was not a particular attack on the movie business by HUAC but had entered the state and national scene … and was winning.”35 The Republicans picked up twenty-eight seats in the House and five in the Senate, and like the Eightieth Congress, elected four years earlier, the Eighty-Second would bring a blast of red-baiting.

SYMPATHY FOR DOUGLAS was in short supply on the set of Ryan’s latest picture, a big-budget war movie teaming him with John Wayne. Flying Leathernecks chronicled the exploits of a Marine aviation unit in the Battle of Guadalcanal, allowing Howard Hughes to indulge two of his great passions — aerial heroics and knee-jerk patriotism. Wayne was currently president of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. Producer Edmund Grainger and screenwriter James Edward Grant, who had created Wayne’s giant hit Sands of Iwo Jima (1949), were active in the Alliance as well. Crusty character actor Jay C. Flippen and on-set screenwriter Rodney Amateau were staunch conservatives. Cornered on the left were Ryan and director Nick Ray. “We often asked ourselves what we were doing on a film like this,” Ryan would recall. “I hate war films.”36

By this time Wayne had been in pictures for twenty years, but in the last few he had really caught fire, giving iconic p

erformances in Fort Apache (1948), Red River (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Rio Grande (1950). In Flying Leathernecks he played Major Dan Kirby, who arrives in Oahu, Hawaii, to take command of the VMF 247 Wildcats unit but prefers not to get too close to men he may have to sacrifice. Ryan was his philosophical antagonist, Captain Carl Griffin, beloved by the men but passed over for promotion. “I cast [Ryan] opposite Wayne because I knew that Ryan was the only actor in Hollywood who could kick the shit out of Wayne,” Ray wrote in a memoir. “That conflict was going to be real, so I’d have two naturals.”37

Ryan wasn’t inclined to kick the shit out of anyone, though his skill with his fists always guaranteed him a wide margin of respect from Wayne, who admired not only his strength but his education and intellect. In any case Wayne was in no position to question Ryan’s patriotism, given his own lack of World War II service; unwilling to let his career languish, Wayne had passed up numerous opportunities to serve with his friend and director John Ford in the US Navy’s photographic unit, which earned him Ford’s eternal scorn. The day after Thanksgiving, principal photography for Flying Leathernecks commenced at Camp Pendleton, where Wayne had shot Sands of Iwo Jima but Ryan actually had drilled recruits during the war.

Flying Leathernecks had been blessed by the military, and the Marines came across with men and materiél; production files show Grainger requesting more than three dozen fighter planes (F6F Hellcats and F4U Corsairs) for aerial photography, another twelve planes for set decoration at Henderson Field, a long list of ground equipment, and the services of one hundred marines. As usual with Hughes’s projects, the story was a mess. Ray actually was working from three different scripts, shooting elements he liked from each, and he hired Amateau to collate them into a single narrative. The result was so disjointed and generic that, by default, the conflict between Kirby and Griffin, over how much empathy to show the men, became the picture’s most interesting story element. Ray was right about the two stars: both men were 6′ 4″ and they filled the frame, Ryan often hovering silently behind Wayne and stealing scenes with his sidelong glances. “It’s all in the eyes,” he would tell his son Tim about the art of acting. “That’s where you do most of your work.”38

The Lives of Robert Ryan

The Lives of Robert Ryan