- Home

- J. R. Jones

The Lives of Robert Ryan Page 16

The Lives of Robert Ryan Read online

Page 16

Barbara Stanwyck signed to play Mae, the smothered wife, and Paul Doug las was cast as her simple, devoted husband, Jerry. Ryan took third billing as Jerry’s malignant friend Earl, the part Joseph Schildkraut had performed back in 1941, and Keith Andes inherited Ryan’s original role as Jerry’s younger brother, Joe. To play Joe’s fiancée, Peggy, Wald cut a deal with Twentieth Century Fox to borrow twenty-five-year-old starlet Marilyn Monroe. At Stanwyck’s urging, Fritz Lang was hired to direct; his brilliant career in the German cinema (Metropolis, M) was now two decades behind him, but he had eked out a second act in Hollywood that included such haunting dramas as Fury (1936), The Woman in the Window (1944), and Scarlet Street (1945). Wald indulged Lang by sending him and cinematographer Nick Musuraca up to Monterey to shoot extensive footage of fishermen and canners at work, with Monroe and Douglas in tow; after three days they came back with ten thousand feet of footage that Wald had edited into a documentary-type preface for the beginning of the picture.

“It was the first time I could convince any producer that we should have rehearsals, as is done for the stage,” recalled Lang. “Because it dealt mainly with three people, you could, in a certain way, rehearse the main scenes…. We marked the exact positions of the camera, its movements and so on. It was wonderful to work with all three: Barbara Stanwyck, Bob Ryan and Paul Douglas.”2 Ryan ranked the director alongside Jean Renoir and Max Ophuls in his ability to recognize and heighten an actor’s best qualities, though in contrast to Renoir, who made everything feel spontaneous, Lang wanted complete control over every aspect of a scene. “He leaves nothing to chance,” Ryan explained. “He plans everything in advance.”3

The one element Lang couldn’t control was Monroe, whose chronic inability to remember her lines began to slow down production almost as soon as shooting commenced in October 1951. She was terrified of Lang, who tried to banish her trusted acting coach, Natasha Lytess, from the set; sometimes the pressure brought out red splotches on Monroe’s skin. Lang watched from behind the camera, fuming, as Stanwyck tried to pull off a complicated stretch of dialogue while hanging clothes on a line and Monroe wrecked the scene again and again. Stanwyck never complained, but Lang took to berating Monroe. At some point Ryan intervened, taking the director aside and urging him to lay off. Ryan took a dim view of colleagues who were unprofessional, but clearly the girl was trying, and haranguing her would only exacerbate the situation. Besides: look at her!

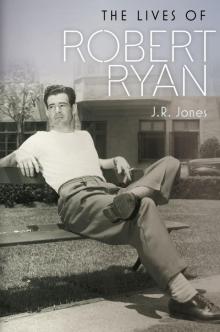

Earl Pfeiffer (Ryan) gets tanked up with Peggy (Marilyn Monroe) in Clash by Night (1952). Ryan took Monroe’s side against director Fritz Lang, and she never forgot it. Franklin Jarlett Collection

Something about Clash by Night brought out the worst in people, and Ryan watched in dismay as the cast, like that of the Broadway production, was riven by professional jealousy. A rumor began circulating around town that Monroe was the young woman posing nude in a new girlie calendar (according to one account, the information was leaked by RKO’s publicity man in the hope of drumming up interest in the new picture).4 Reporters flocked to the set, ignoring the forty-four-year-old Stanwyck as well as Douglas and Ryan. Monroe had sat for the photo back in 1949, when she was still unknown and needed the fifty dollars for a car payment. “The calendar business was no secret in Hollywood, but the public didn’t know about it,” recalled Ryan. “One of the reporters asked me, ‘Where’s the babe with the big tits?’ He didn’t even know her name.”5 At one point Wald received an anonymous call from someone demanding $15,000 to keep quiet about Monroe’s deep, dark secret; instead the producer wanted to put her name above the title with those of the other three stars.

Earl (Ryan) moves in on Mae Doyle (Barbara Stanwyck), his best friend’s wife, in Clash by Night (1952). Franklin Jarlett Collection

Lang remembered their reaction when they heard the news. “Douglas said, ‘I will never give my permission, never! Who is she? A newcomer! She will never make the top grade.’ Ryan didn’t say anything, but Barbara said, ‘What do you want — she’s an upcoming star.’”6 Monroe got her above-the-title billing, fourth after Ryan. Douglas was furious; on the set, after Monroe referred to him in passing as “Paul,” he ordered her to address him as “Mr. Paul Douglas.”7 According to Keith Andes, Stanwyck eventually grew frustrated with Monroe, who would “always come in late and all f_____ up. Stanwyck finally said, ‘Look, unless she’s working, keep her off the set. I don’t want her around.’ After all, Barbara was a good-humored woman but she was also a professional.”8 After Monroe’s death, Stanwyck would remember that she “drove Bob Ryan, Paul Douglas and myself out of our minds … but she didn’t do it viciously, and there was a sort of magic about her which we all recognized at once.”9

Ryan tried to stay above the fray, just as he had with Lee Cobb and Tallulah Bankhead. He had a much better part this time, though Earl Pfeiffer would be his third heavy in a row after The Racket and Beware, My Lovely. A projectionist at the local movie house, Earl despises his wife, a burlesque performer who is constantly on the road. “Someday I’m going to stick her full of pins, just to see if blood runs out,” he tells Mae. Earl can be an embarrassment — at a restaurant, as a joke, he pulls his eyes into slits and jabbers obnoxiously in mock Chinese — but Mae is attracted to his hard body and cynical talk, and tired of the dully unimaginative Jerry. When Mae and Earl go into a clinch, Mae hungrily reaches up under the back of his wife-beater, a sharply sexual moment probably inspired by the recent release A Streetcar Named Desire. Lisa Ryan would remember her mother always getting angry when Stanwyck’s name came up.10

To produce Clash by Night, Wald and Krasna had chosen Harriet Parsons, one of very few women in the business and the daughter of gossip columnist Louella Parsons. Harriet persuaded her mother to write a column on Ryan, her first since the 1948 profile in which she had hinted at his affair with Merle Oberon. This time around Louella was squarely in his corner: “With all this talk of divorce and scandal in Hollywood, Robert Ryan is almost too good to be true. None of these evils has ever touched him, and I’m going to put my neck out a mile and say I’m sure none ever will.” Louella visited the set to watch Ryan play a scene as Earl, and according to the column, Ryan asked her afterward, “How did you like me as a home wrecker?” The complex social transaction was completed when Ryan credited Harriet for having persuaded him to take the role. “When Howard Hughes first sent word that I was to play this dubious gentleman for Wald and Krasna, I had plenty of reservations. I had never been a no-good character who steals another man’s wife.”11

Production wrapped in early December, leaving Ryan with a two-month interim before his next job. When the story about Monroe’s nude photos finally broke the next year, the young actress made a frank statement about it that disarmed critics, and as Wald and Krasna had hoped, the publicity drove ticket sales for Clash by Night, which connected at the box office and drew good reviews as well. Seven years later, when Ryan was shooting Lonelyhearts at Samuel Goldwyn Studio, he would take his son Cheyney over to meet Monroe as she filmed Some Like It Hot on a neighboring soundstage, and the boy would be surprised by how warmly she received his dad.12 Word had gotten back to Monroe that Ryan took her side with Lang, and she never forgot it. “Poor kid, she was so bewildered,” Ryan said after her death. “Right after the picture was finished she sent me a big box of candy with a very touching note.”13

Once 1952 arrived, the Ryans grew busy again with the Oakwood School. After searching fruitlessly for a better facility than the temple building, Ryan and Ross Cabeen decided to buy land and put up a building themselves. The parcel they chose was on Moorpark Street in North Hollywood, a few miles southwest of the Ryans’ home. “Circling the property on two sides was a dry wash as yet unreclaimed by the Flood Control System; it still presented a sandy bottom lined with scrub willows,” wrote Jessica in her memoir. “The property itself consisted of close to three acres of ground with a magnificent stand of eucalyptus trees down one side bordering the wash.”14

The two men bought the prope

rty for $6,500 and went before the parents’ group proposing that everyone contribute toward a building fund. According to Jessica, this idea met with controversy because the parents, now numbering about thirty-five, would neither own the property nor have any legal power over the buildings’ disposition — only Ryan, Cabeen, and Sid Harmon had incorporated the school. With or without the parents’ participation, Ryan and Cabeen resolved to go ahead and construct two classroom buildings on the lot.

Their first hurdle was to win a zoning variance from the city, which meant collecting signatures from all the neighbors. Whenever Ryan had a day off from work, he and Cabeen spent the afternoon making the rounds with their petition. One tough customer, wrote Jessica, told them he didn’t like actors, children, or Jews, but after several visits they caught him after a few drinks, listened politely as he recalled his days as a Klansman back in Illinois, and finally won his signature by promising to “keep them out.”15 A building fund of $14,000 was established, heavily endowed by the Ryans, Harmons, and Cabeens, and construction began in April. Instead of laying a cornerstone, the parents staged a little ceremony in which each child at the school laid a concrete block on one row of a wall.

With production at RKO slowing to a crawl again, Hughes loaned Ryan out to Universal-International for a two-picture deal: the first, Horizons West, began shooting in February 1952, and the second, City Beneath the Sea, followed soon afterward, keeping him busy through early May. The deal must have seemed like a good move: he would get top billing in both films, which would be shot in Technicolor and directed by the capable Budd Boetticher. In Horizons West he plays a former Confederate soldier who returns to his native Austin, Texas, and, frustrated in his plans to establish himself in business, turns to horse rustling and amasses a small fortune; Rock Hudson is his brother, whose new job as sheriff of Austin puts them on a collision course. (“He’s not getting married again soon,” Ryan would remark whenever Hudson’s name came up.)16 City Beneath the Sea teamed him with Anthony Quinn in a tale about deep-sea divers. Universal was a lesser major studio, carried by the tireless Abbott and Costello, yet it was in better shape than RKO.

Jessica plants a tree at the Oakwood School in North Hollywood as Tim and Bob look on. “More than anyone else, she was responsible for Oakwood’s survival,” wrote the school’s director, Marie Spottswood. Robert Ryan Family

The first time RKO had loaned Ryan out — to MGM for Act of Violence — all hell had broken loose in his absence, and the same thing happened again as he was shooting at Universal. Variety reported in February that both Edmund Grainger Productions and Wald-Krasna Productions were at wits’ end, waiting endlessly for Hughes to approve their scripts.17 Then, two months later, as the American Legion and other right-wing groups massed for another anticommunist assault on the entertainment industry — not just movies this time but also TV, radio, and theater — Hughes shut down production on the Gower Street lot for a second time, announcing that he would conduct a systematic purge of communists and their sympathizers from the studio ranks. Industry observers wondered if this were just a prelude to Hughes selling his interest in the studio; the president of the Screen Writers Guild, which had been feuding with Hughes over giving screen credit to blacklisted writer Paul Jarrico, argued that Hughes had “thrown a mantle of Americanism over his own ragged production record.”18

As part of this crusade, Hughes established a new security office at RKO to screen all employees for suspect activities or associations. Many were suspended, and at some point Hughes must have made up his mind that Robert Ryan would have to go. Publishing in The Worker, launching this bohemian school out in the Valley, stumping for the Progressive Citizens of America, American Civil Liberties Union, and United World Federalists — now that Hughes had to put up or shut up, he may have decided Ryan was too far over the line to be defended. Before long the actor had a new contract with RKO stipulating only that he make one picture a year. For the first time since signing with the studio in 1942, Ryan was a free agent.

THE BREAK WITH RKO opened up a world of possibilities for Ryan — he could return to Broadway, even play Shakespeare — but more immediately he needed to land a good picture, just to prove he was still bankable. Once he found himself on the open market, he gravitated immediately toward Dore Schary, the liberal producer who had cast him in Crossfire five years earlier. Since fleeing the Hughes regime at RKO, Schary had returned to his previous employer, MGM, where he kept up the good fight with such stark, serious-minded dramas as Battleground (1949) and The Red Badge of Courage (1951). In a studio shake-up he had recently replaced the aging Louis B. Mayer as president, and now he came through for Ryan with a plum assignment, supporting James Stewart and Janet Leigh in Anthony Mann’s harsh psychological western The Naked Spur.

Ryan had never cared much for westerns, and they were hell to make, with remote locations and strenuous action shots. But the Naked Spur script, by first-timers Sam Rolfe and Harold Jack Bloom, read like a chamber drama; aside from a brief shootout with some Blackfoot Indians, the action was re stricted to only five characters, all locked together in a treacherous mountain journey. Bounty hunter Howard Kemp (Stewart) has arrived in the Rocky Mountains searching for Ben Vandergroat (Ryan), who’s accused of murdering a marshal in Abilene, Kansas. Aided by an elderly prospector, Jesse Tate (Millard Mitchell), and a disgraced cavalryman, Roy Anderson (Ralph Meeker), Kemp manages to capture the outlaw and his unwitting young accomplice, Lina (Leigh), but as they cross the mountains on horseback to collect the reward, Vandergroat begins sowing discord among the three men.

The role had originally been earmarked for Richard Widmark, and Ryan was happy to have aced him out: here was a smart, layered character who threatened to turn the pat morality of most westerns on its head. Ryan played him as a cracker-barrel philosopher, his homespun wisdom dispensed in a mirthless chuckle. When a frustrated Kemp offers to shoot Vandergroat on the spot, the outlaw peers up at him, his brow lined with the years, and replies, “Choosin’ a way to die, what’s the difference? Choosin’ a way to live — that’s the hard part.” Ryan tosses off this Will Rogers dialogue with ease, yet it masks an ugly soul. Near the end of The Naked Spur, Vandergroat succeeds in peeling away the old prospector, Tate, with the promise of a gold mine, then wrestles away his rifle and coldly murders him. “Look at him, lyin’ there peaceful in the sun,” he tells the horrified Lina, slipping back into his gentle drawl. “Ain’t never gonna be hungry again, want anything he can’t have.”

Four years earlier Ryan and Leigh had shared an electric scene together in Act of Violence; The Naked Spur gave them much more screen time, and they worked well together. The ambiguous relationship between the outlaw and his young charge turns out to be the most troubling aspect of The Naked Spur. Vandergroat presents himself as the only family Lina has left, and they’re tenderly affectionate with each other. Bound at the wrists, he drapes his arms over Lina’s head, even brushing her forehead with a kiss; plagued by a sore back, he periodically calls on her to “do me,” and she faithfully massages his shoulders. At the same time he’s not above exploiting her sexually, especially after he realizes that both Kemp and the low-rent Anderson are taken with her. “The more they look at you, the less they’ll be lookin’ at me!” he whispers to her in a quiet moment.

The entire film was shot on location in the San Juan Mountains, near Durango, Colorado, from late May to early July. The cast was lodged about fifteen miles from town in a group of cabins at El Rancho Encantado. “It was a congenial, pleasant, cheerful group, and I believe everyone thoroughly enjoyed themselves,” Leigh recalled.19 Jimmy Stewart and his wife, Gloria, threw an anniversary party for Leigh and Tony Curtis, during which Curtis buttonholed Ryan for a program in which they would visit with underprivileged kids in East Los Angeles. Ryan was joined by Jessica and the children; the boys got to watch stunt work being filmed, and one evening the family drove into town and caught an early show of Best of the Badmen at a drive-in theater. It was the first t

ime the children ever saw their father on-screen.20

Ryan loved working with Stewart — a class act who, on one occasion, finished his own shots early but stuck around all afternoon feeding lines to Ryan and Leigh from behind the camera. But the best professional relationship Ryan would carry away from The Naked Spur was with director Tony Mann. “ What made Mann so brilliant,” remembered Ralph Meeker, “was his ability to pick a backdrop that might be green and lush or barren and stark, or a rushing river, and he could put his actors against these backdrops, and it all became one.”21 Mann’s camera sense was superb; he knew not only how to tell a story in pictures but how to tell it in landscapes. He liked vertiginous overhead shots and put his actors through quite a gauntlet as they rode and climbed, using doubles only when absolutely necessary. Leigh would recall the tall rock above a roaring river where she, Ryan, and Stewart filmed the climax: “The ultimate panic was being on top and peering down down down at the angry water and rocks below. With no guard rails, with no nothin’! … The fear we registered was genuine.”22

Tall and athletic like Ryan, Mann had grown up in San Diego and bounced around RKO and the low-rent Republic Studio before distinguishing himself with some dynamic crime pictures (Raw Deal, Border Incident, Side Street) and Stewart’s hit western Winchester ’73. No one could ever get a word out of the guy, though Ryan liked this. “I understand that for certain people it became very difficult to work with him,” he later said. “For young people especially, since they love to talk about their character for hours…. There are certain actors who, to light a cigarette, need to create a back story. Me, I prefer not to talk.”23 He and Mann would make three pictures together, all of them excellent, and Ryan would rank his performance in The Naked Spur as one of his best. It gave him just what he needed at this career juncture: a chance to shine as an actor, working alongside the best in the business.

The Lives of Robert Ryan

The Lives of Robert Ryan